Layers Don’t Have To Be Where 3D-Prints Fail

A new way of 3D printing to achieve stronger parts without adding additional material

Background

Globally, the most widespread 3D printing method uses fused deposition modeling (FDM), in which a thermoplastic filament is deposited layer-by-layer to create parts. These printers are affordable, capable of creating high-quality parts, and widely used by hobbyists and commercial users alike.

However, FDM printing is inherently limited by poor layer adhesion: printed layers are deposited sequentially onto cooler ones, which can lead to insufficient thermal bonding between layers. Accordingly, when a tensile, compressive or shear force is applied, mechanical failure tends to initiate along layer lines. This anisotropic weakness imposes design constraints, as forces have to be minimized along layer lines, and often requires additional material to be added to parts.

This problem is especially relevant in industries where the weight and strength of 3D printed parts are fully leveraged, including the aerospace and the automotive industries. For instance, applying FDM printers to create extraterrestrial habitats, tools for space stations, drone components, and automotive components all rely on the load-bearing of parts being efficiently utilized.

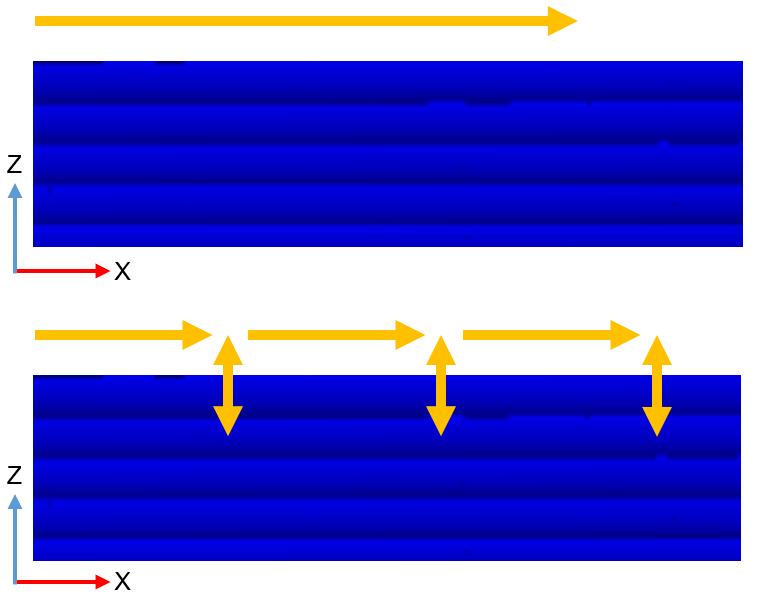

Figure 1: Movement of the printhead (orange arrows) using a standard technique (top), and technique with Z-axis modulation (bottom).

Methods

This project analyzes whether modulating the motion profile of a standard FDM printhead can improve the mechanical properties of parts. The approach is to introduce periodic vertical (Z-axis) movements into printing (Figure 1), thereby reheating and increasing the surface area of layers to facilitate their bonding. In these movements, the printer does not deposit additional plastic, which allows the modulated and unmodulated parts to have the same weight.

To implement this modulation, I developed a Python G-code parser post-processing script, which allows the modulation to be applied with any FDM 3D printer. The script can be easily integrated into a standard slicer and is parameterized to accommodate different spacing/depth settings of vertical movements.

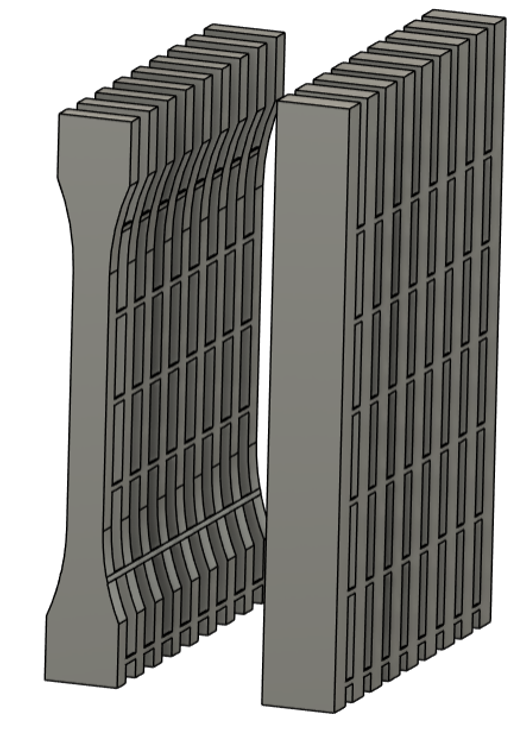

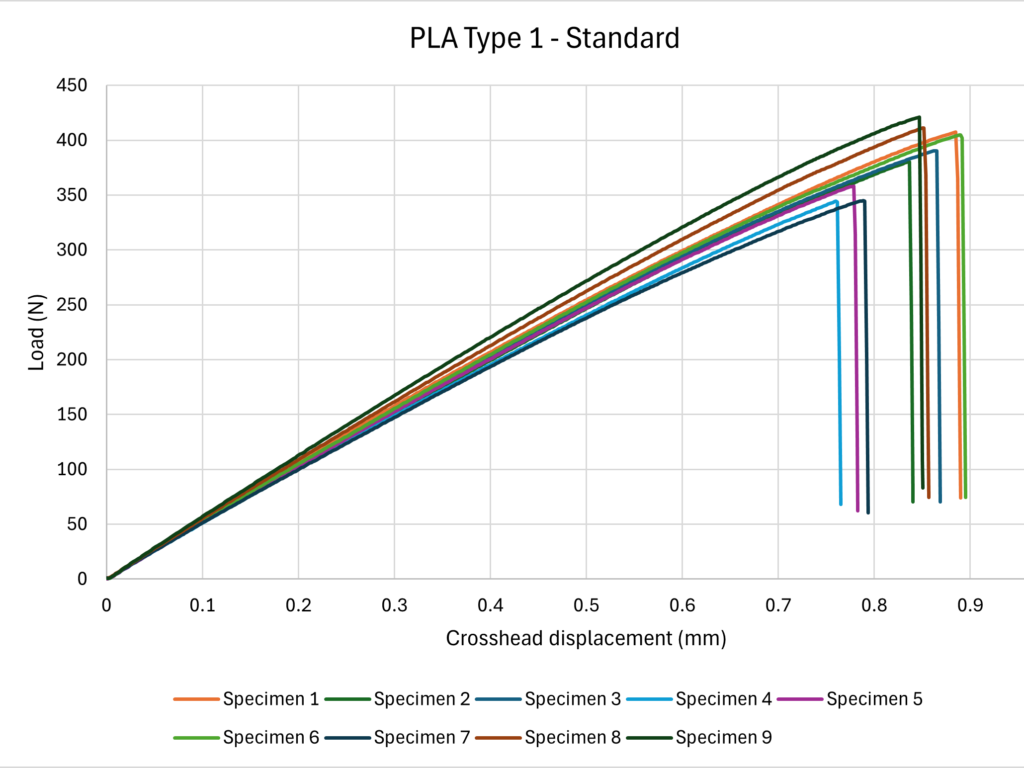

For testing, ISO 527 and ISO 179-1 samples (Figure 2) from 11 plastics were tested on a universal test machine and Charpy impact test machine. Preliminary tests were performed on a home-made apparatus, after which tests were performed on a university’s professional, calibrated equipment. For standardization purposes, this poster exclusively references measurements made on the professional equipment. 281 successful tests were performed and analyzed (123 pcs ISO 527, 158 pcs ISO 179-1); the results from one plastic (PLA Type 4) were lost due a failed export of measurements from the test machine

Figure 2: Illustration of samples used in testing.

Testing

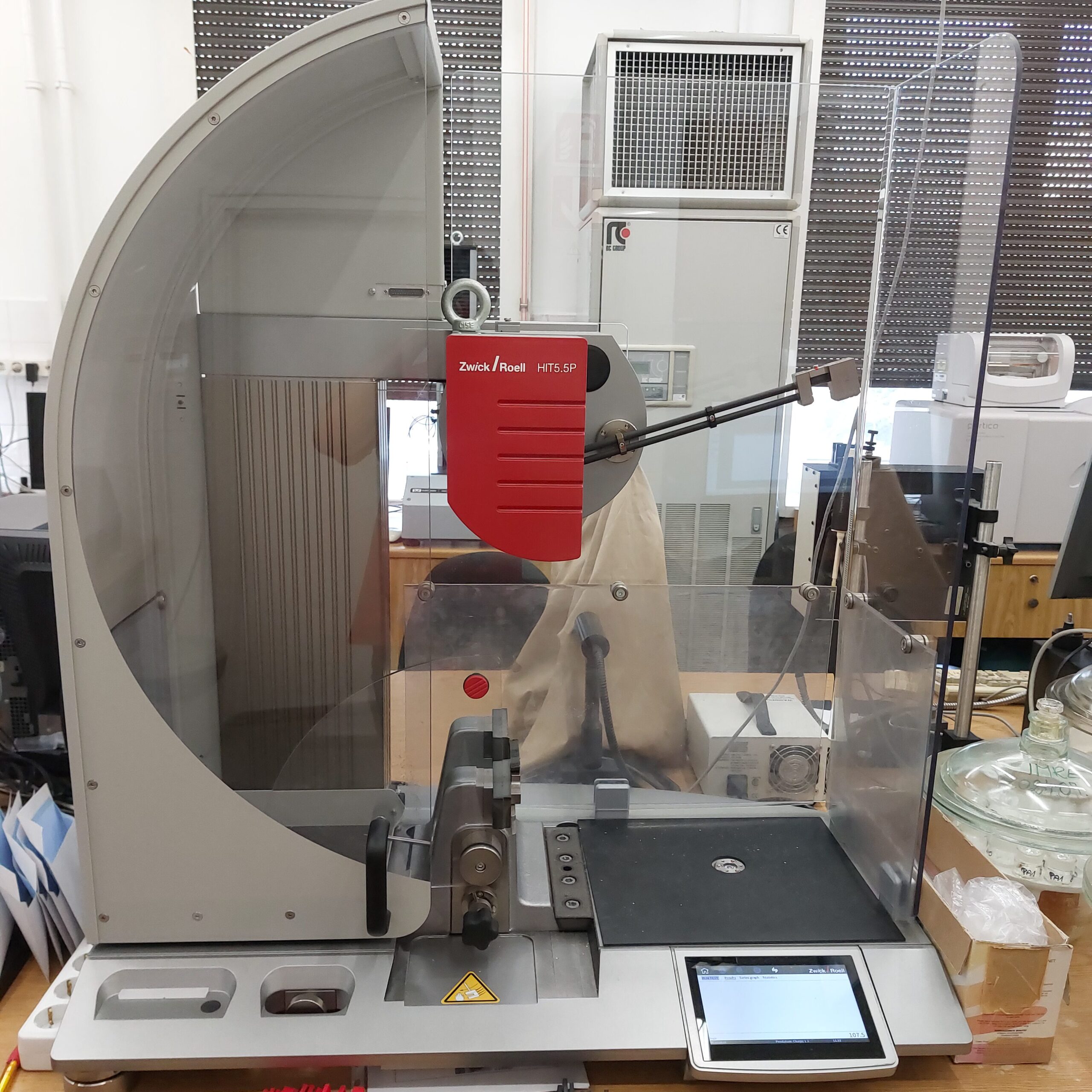

Testing was initially performed on a homemade apparatus. However, as the project progressed I had the chance to redo tests and validate results on professional testing equipment at the Budapest University of Technology (BME).

Professional apparatuses used for testing (UTM left, Charpy Impact Test right).

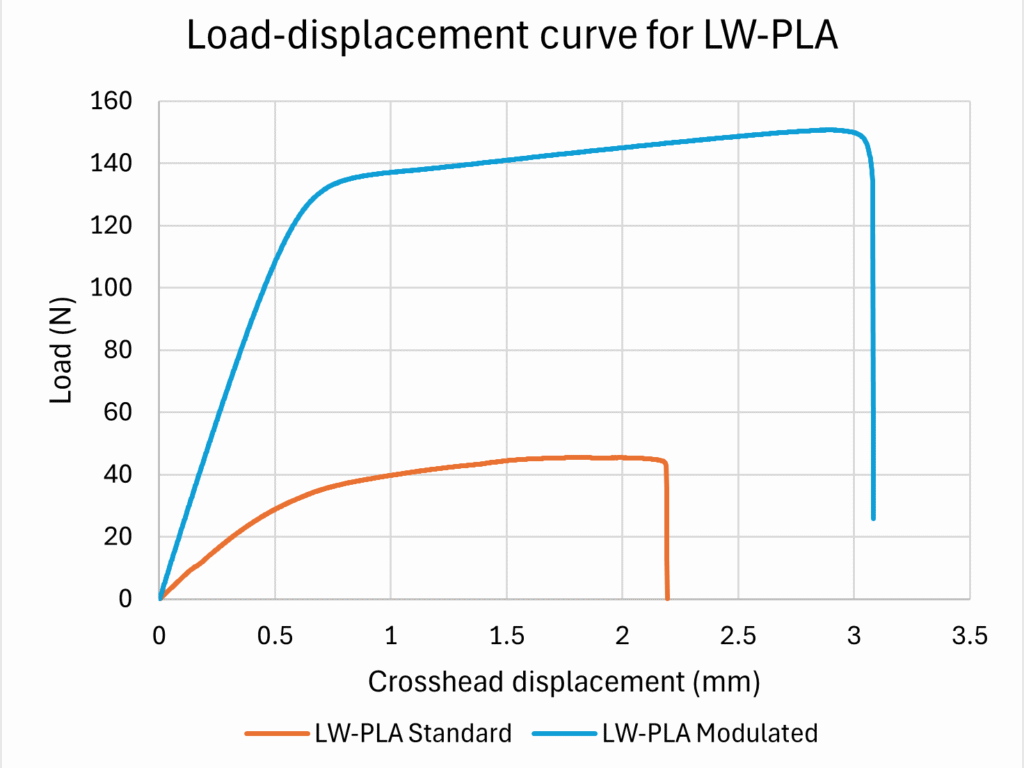

Examples of load-displacement curves used for analyzing the technique.

Results

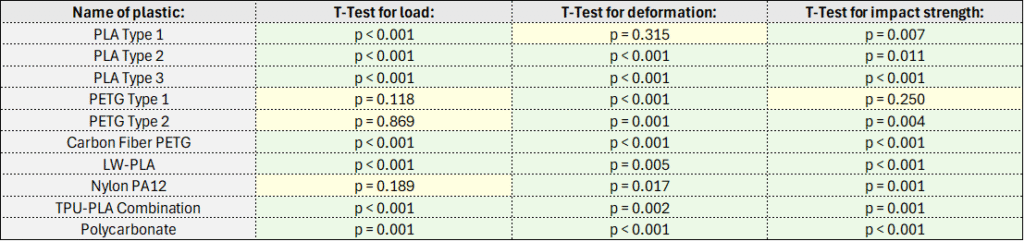

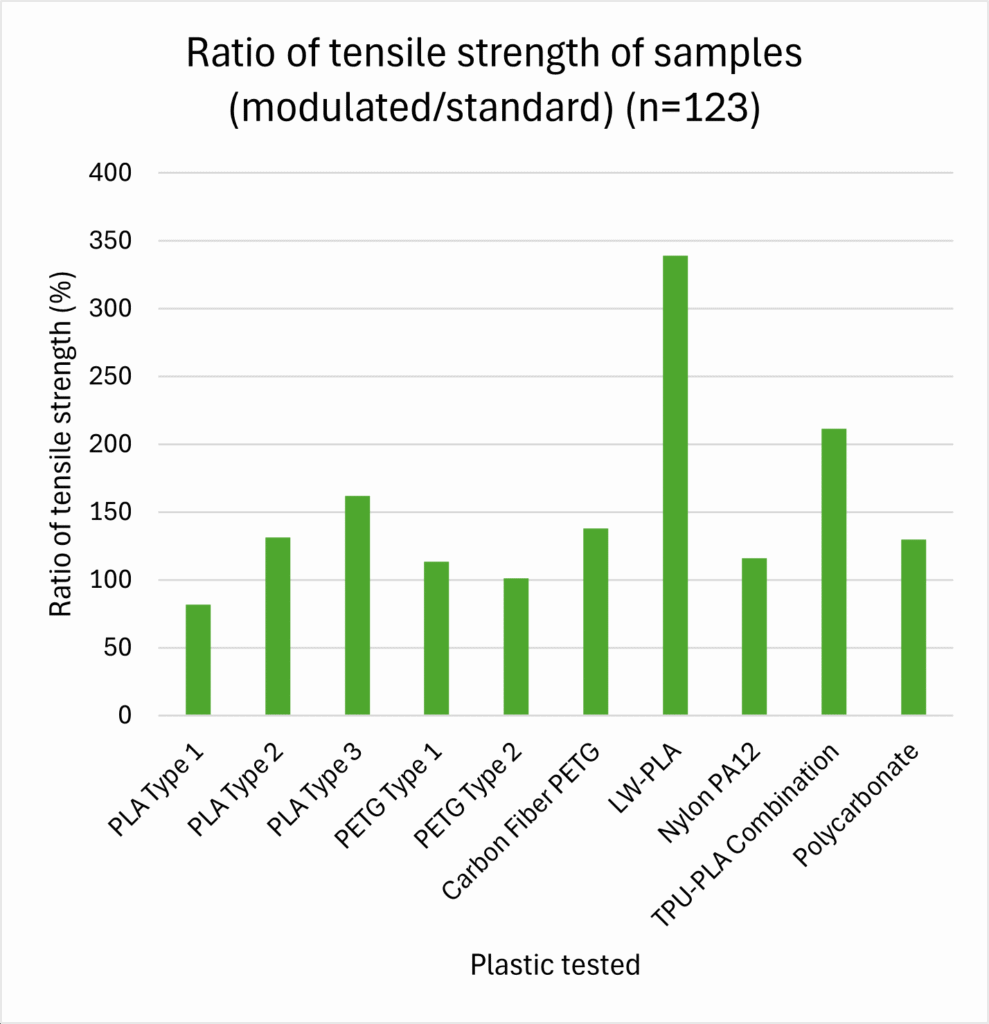

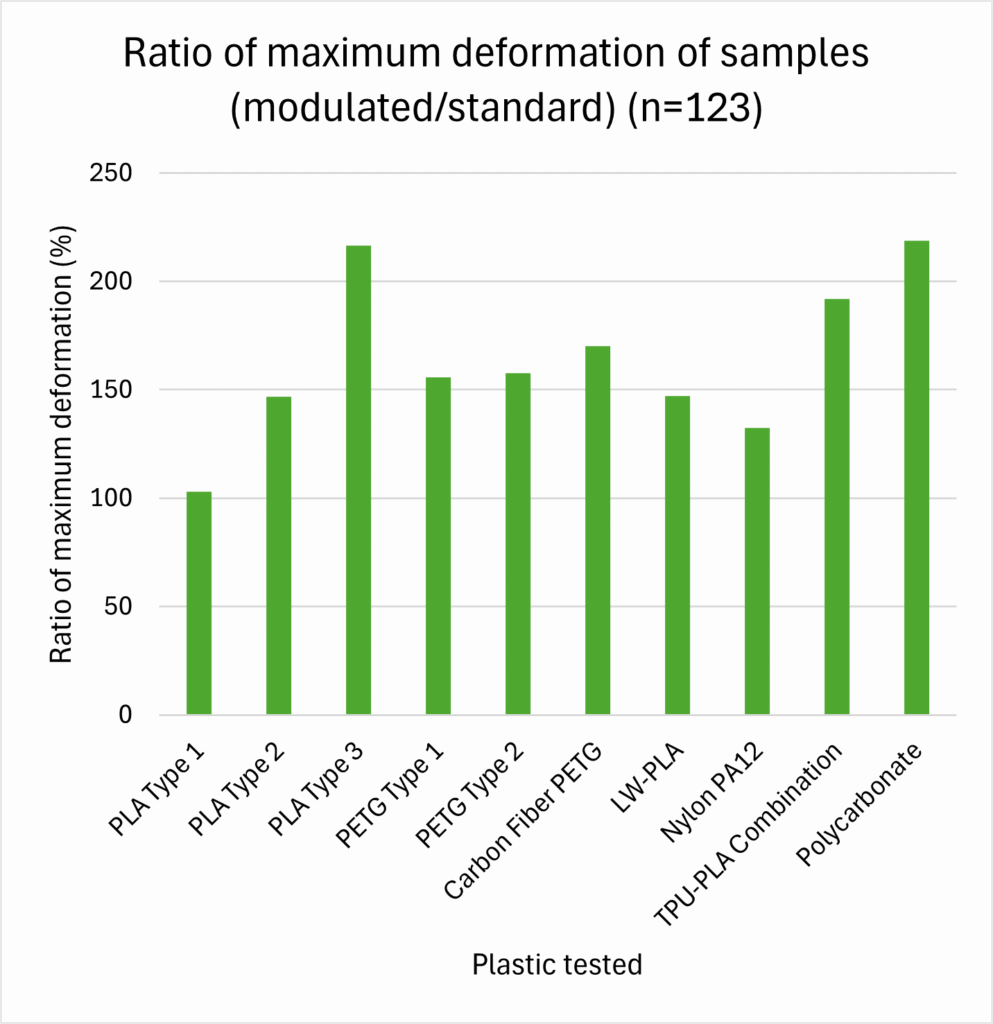

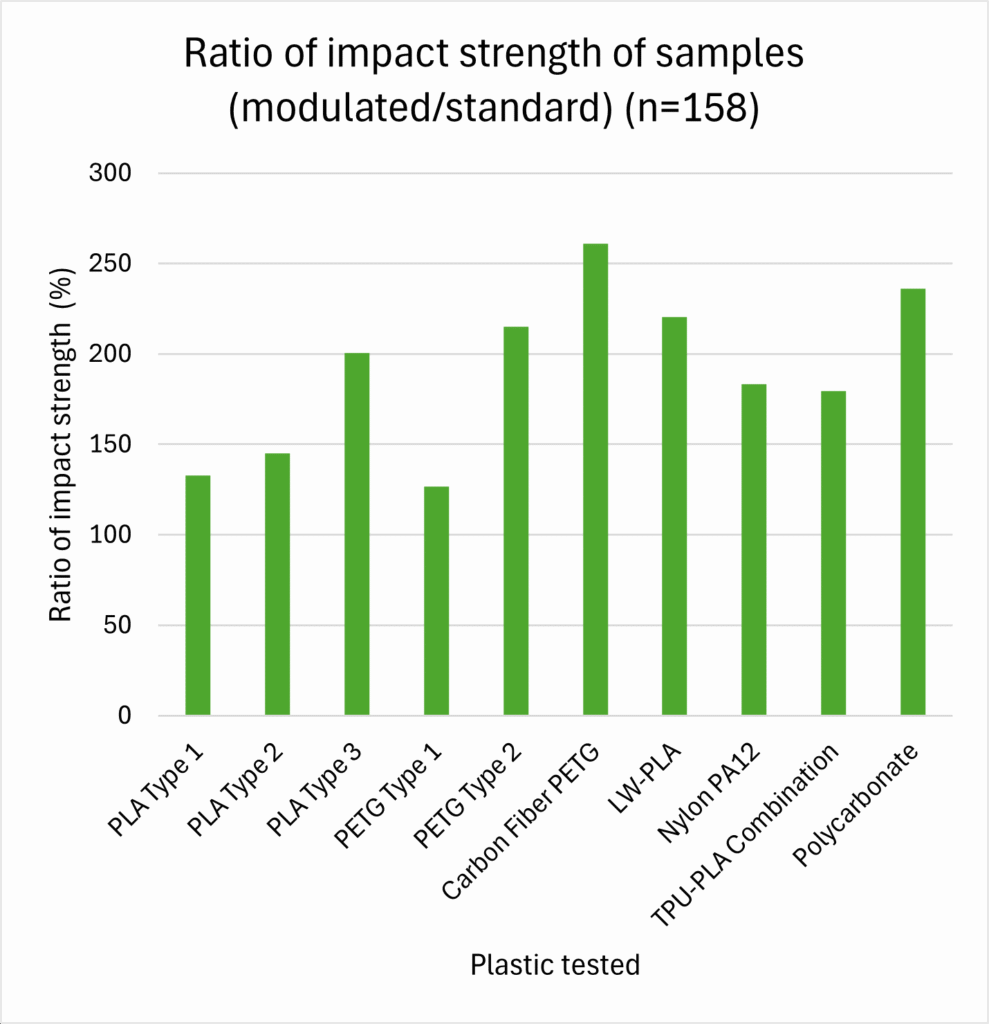

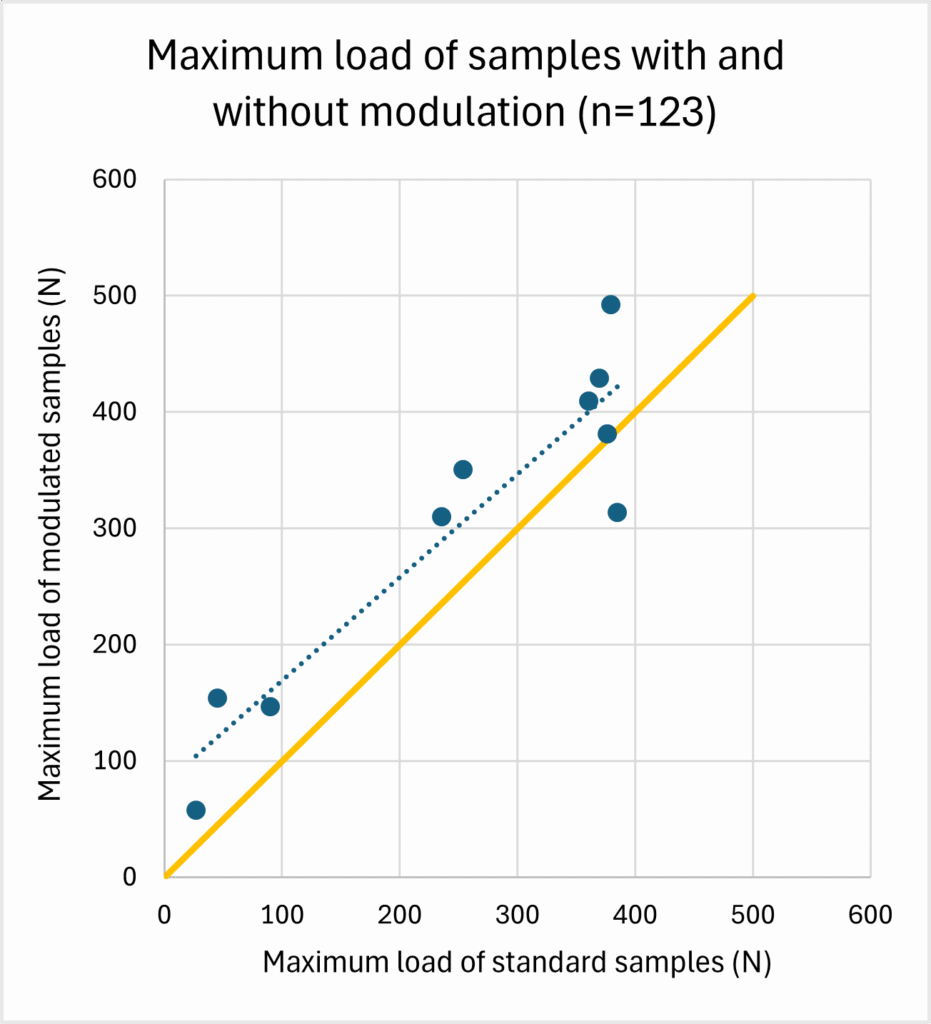

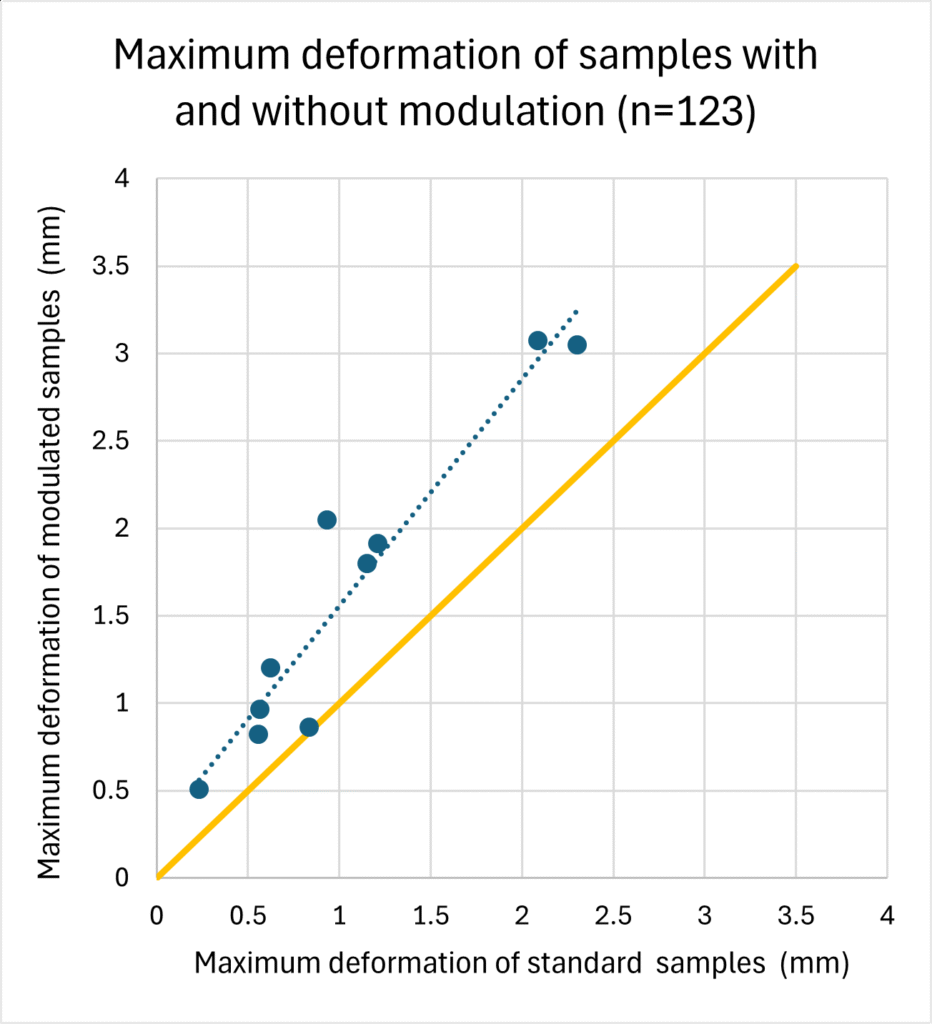

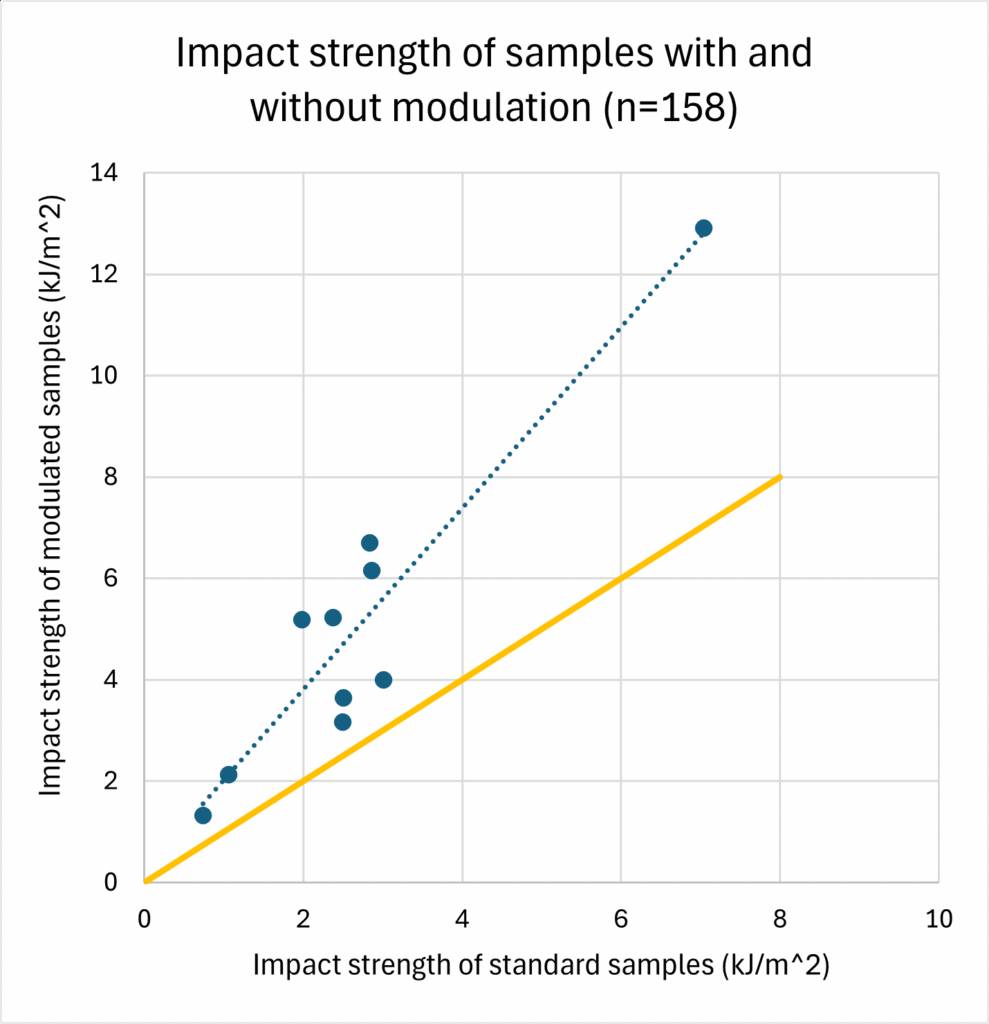

The technique proved to significantly increase the tensile strength, maximum deformation before failure, and impact strength of several plastics (Table 1). Compared to standard parts printed under identical conditions, modulated parts showed, on average, 152% of the tensile strength, 164% of the maximum deformation, and 190% of the impact strength (Figures 3 and 4). These increases were even more notable with engineering and specialized filaments, which showed 187% of the tensile strength, 172% of the maximum deformation, and 216% the impact strength compared to standard samples printed under identical conditions.

Table 1: P-values for all tests performed

Figure 3: Ratio of tensile strength (left), maximum tensile deformation (middle), and impact strength (right) for all plastics tested.

Figure 4: Tensile strength (left), maximum tensile deformation (middle), and impact strength (right) comparison between standard and modulated samples for all tested plastics.

Discussion

The results of the modulated 3D printing technique are highly promising, demonstrating that the technique can increase the tensile strength, deformation before failure, and impact strength of both common and specialized/engineering filaments—without adding additional material. This signals that the technique allows for lighter, stronger, and less brittle parts to be manufactured. The technique’s improvement of the mechanical properties of specialized and engineering filaments is particularly significant, as these plastics are widely used and already optimized for mechanical performance. For example, the impact strength of Nylon PA12—already the strongest filament tested—more than doubled. Additionally, the improved bonding between flexible TPU and rigid PLA enables 3D prints to have embedded compliant mechanisms.

Because of the software-based approach, the technique can be applied to virtually all FDM 3D printers and 3D models; the G-Code parser developed is versatile, modifiable, and effective.

The main limitation is that the technique increases the print time of parts. Control tests where the print speed for unmodulated parts was decreased to the same speed showed that the mechanical improvements were not attributable to the slower printing.

Conclusion

If widely adopted, the technique could increase the applicability of 3D printers, leading to more efficient designs and a sizable decrease in plastic waste creation. The method could be used to strengthen both industrial parts (such as car or aircraft components) and also home 3D prints.